Overview of TGfU

|

Teaching Games for Understanding (TGfU) is aimed to develop participants understanding the strategies and tactical complexities of the game as well as knowing when and where to utilize and apply the techniques of the game (skilled performance). Although game teaching approaches that linked techniques and tactics had roots in the work of Mahlo (1974) and Deleplace (1969/1979) in Europe, the TGfU movement originated at Loughborough University 20 years ago by former practitioners turned researchers, David Bunker and Rod Thorpe, (1982) along with Len Almond, who became tired of watching teachers teach techniques only for them to break down in game play. They believed that students could have a good game without much technical expertise, although they never stated that technical skill was unimportant for successful game play. To support this view they argued that the focus of instruction should be based on cognitive outcomes such as ‘what to do’ and ‘when to do it’ as well as the actual ‘how to do it’ associated with motor performance that had long been the focus of many teacher’s instruction.

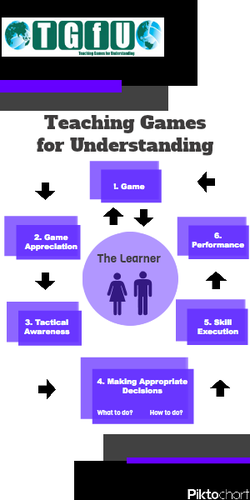

They further argued that games fostered more achievement motivation for the students. With playing games students were placed in a less intimidating environment than isolated technique practice as participants could make mistakes in the game that may go unseen to the naked eye, whereas is row line practices or ‘drills’ they would be singled out as poor performers. Finally, Bunker and Thorpe believed that a lot of children left school not knowing how to play a game because they were not taught how to in terms of strategy and tactics. Therefore, this led to students leaving school and not continuing to play games that teachers had spent so much time teaching them. By teaching “through the game and in the game” Launder (2001, p.55) at least students would know the game set up, the rules and strategies/tactics so they could play them on their own. The traditional technical-orientated approach which focused on a ‘technique’ orientation did not teach them this knowledge. This further has implications today where the physical education profession is encouraging the promotion of active lifestyles outside of school and into adulthood. In terms of the actual TGfU model (see image courtesy of http://tgfuinfo.weebly.com/), the learner is placed at the center of the learning process, which immediately affords the learner a more holistic view of the game. When playing games or a game form, it is hoped that players then develop an appreciation for the game and learn the rules alongside the tactics/strategies needed so they can develop tactical awareness in order to make effective decisions to solve certain problems the game poses. Once decisions (what to do) have been made (e.g., which technique to use), players would then execute the technique (when and how to do it) in the game context (skill). Game Performance is elevated if the pupil executes the appropriate technique(s) effectively and at/in the correct time frame. In TGfU therefore, development of skill comes second after the teacher and students see the need for skill within the game. This skill development can be applied within the game that is ongoing by adding exaggerations (such as ‘no-go zones’ or using multiple goals) or by using skill drills (Metzler, 2000), a policy advocated by Griffin, Mitchell and Oslin (1997) in their adapted version of the TGfU model, the Tactical Games Model. The You Tube videos below explain more about the TGfU approach. If you want to know more about how to teach using TGfU for specific game categories, see the following link |

|